Armed with appropriate refreshments and entertainment for the end-of-term party, we met for the final time in the wonderful Watson Gallery on Monday 27th November. We read and discussed a selection of poems which in different ways used mud, soil, or earth to contemplate themes of transience, nostalgia, mortality, embodiment, sensory engagement, warfare, regionality, ritual, heritage, and more. Many thanks to everyone for their thoughtful contributions to the conversation!

Below, Charissa's photos of Simon's poetic illustrations.

Showing posts with label Recap. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Recap. Show all posts

Monday, November 27, 2017

Wednesday, November 15, 2017

Recap - Mountain

Our third meeting took place on a chilly Monday evening, which brought at least a hint of the Canadian climate to Cambridge. Charissa gave a fabulous, wide-ranging introduction to the set readings, putting them into a wider context of the role of mountains in geology and tourism; in ideas and ideals of masculinity and conquest; in the presence of women in the literary and photographic record of early 20th-century mountaineering; in the variety of ways in which women participated in climbing, photographing, collecting, reporting, or conversing; and through the particular biographies of some of the extraordinary women whose works we read.

We learned about the role groups such as the Alpine Club of Canada - from whose journal the selected readings were taken - had in putting a Canadian 'stamp' on mountaineering, ensuring that Canadians, too, could claim 'first' ascents. We learned of the social cohesiveness of these clubs, with most members being middle-class/professionals; and that there were a significant number of women who joined. We learned how the Canadian-Pacific railway made the Rockies newly accessible for trade, travel, and exploration, and how an economy was established along its route. 'The Alpine Club of Canada' gave a sense of the possibilities of patriotism and participation the group hoped to foster.

Considering

the appreciation of mountains from the 18th/19thC as locations for

especially picturesque or spiritual experiences, we compared how these

women often spoke about their physical, tactile contact with mountains.

Mountaineering was an overtly embodied endeavour (as 'A Graduating Climb' detailed): a combination of 'the

flesh-stuff and the soul-stuff', which had - so these writers claimed -

benefits for health, including for female bodies, as laid out by 'Mountain Climbing for

Women'.

We looked in more detail at the biographies of Mary Vaux (see the marvellous photographs online at 'Mary M. Vaux: A Picture Journal': lots of wonderful mountaineering images; Her botanical illustrations are also on Wikipedia), Mary Schaffer (more on her here) and Mollie Adams, who suffered an unfortunate encounter with Rudyard Kipling, and Elizabeth Parker.

Overall, we felt privileged to have, through their writings, photographs, and records, joined these women on their ascents and adventures. Next time: mud, glorious mud.

Wednesday, November 01, 2017

Recap - Ground

|

| Edmond Halley advertises the Reading Group's meeting |

We explored how both texts used literary strategies to present their events or reasoning processes as likely extensions of currently-known observations, creatures, or societies. We thought about fantastical travel narratives and their relationships with other genres: how speculative fictions as well as tours of underworlds were used to frame understandings of what might be found underfoot. We saw how the two texts in question connected what we might call intraterrestrial writings with extraterrestrial writings, as the interior of the Earth was compared with other planets, whether Saturn's rings, the Moon, or new planets waiting to be discovered.

The evening ended with a wonderful tour of Simon's lab - and other highlights of the Department of Earth Sciences, including the dinosaur-clad library bookcases - where we were able to glimpse the current work ongoing to illuminate changes in the Earth's magnetic field.

Next time we ascend the Canadian Rockies.

Tuesday, October 17, 2017

Recap - Stone

One of the most significant, lengthy, and complete ancient works, the Natural History attempted to be an encyclopaedic rendering of contemporary knowledge about the contents, origins, usages and properties of the natural world. Indeed, we found, the books were more than a catalogue of rocky descriptions, being accounts, stories, and recipes which dealt with stones in all their manifestations:

- As part of a bigger natural whole

- As sculpture, art, and buildings

- As having intrinsic aesthetic properties

- As coming from specific places

- As useful: in processes, in remedies

- As magical or marvellous

- As mythical

- As tasty

- As fossils

- As changeable

- As similar and simile

Throughout, we considered three themes or questions on the compilation and presentation of natural knowledge, as the text exhibited differing voices, digressions, and tensions:

- Authority: whose?

- Description: how?

- Meanings: why?

Next time we venture underground...

|

| Making use of geological apparatus to sieve cork and sediment from wine... |

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

Recap - Sea

Thanks to the mild summer evening, we were able to hold our last meeting of term once more on the margins of the water, in the riverside gardens of Darwin College. Marie introduced our two readings by Rachel Carson, taking us through Carson's career, the relationship between scientific practice and science-writing in the mid-twentieth century, and women in science. As the introduction to Lost Woods revealed: 'What is remarkable is not that Carson produced such a small body of work, but that she was able to produce it at all' (xi).

We thought about the literary strategies Carson employed in 'Undersea', and its similarities with and differences from 'The Edge of the Sea': her precision or vagueness, imagery and comparisons, and evocation of previous classics of scientific literature, from Lyell's Principles to Darwin's Origin. We discussed Carson's ecological and environmental awareness, and her striking early illustrations of the interconnected effects of climate change. We went on to consider what was known about the depths of the sea (or les profondeurs, in Marie's favoured terminology) at the time Carson was writing, and how new discoveries of phenomena such as hydrothermal vents have reframed our understanding of the deep as a more active and energetic place, rather than a gloomy stillness punctuated by monstrous creatures (pictures of which Marie showed us). Carson's mention of foraminifera provided Simon with an opportunity to bring along some fabulous actual and 3D-printed examples from the Department of Earth Sciences' teaching collection (photographs below).

Overall, a fantastic end to what has been a thoroughly enjoyable term's conversations on and around four marvellous readings. Next stop, Earth...

Tuesday, June 06, 2017

Recap - Ice

%2C_1861_(color).jpg)

Our third meeting of term took to the Victorian stage and the Arctic wilderness as we discussed The Frozen Deep by Wilkie Collins (with significant input from one Charles Dickens). Simon and his cardboard cast gave a wonderful introduction to the play's influences (notably the 1845 Franklin expedition and the lost Erebus and Terror, the great mystery of which continued to fascinate audiences back in Britain), its writing, dramatis personae, and initially rapturous reception in 1856 (even the set's carpenters were weeping), before a failed attempt at a revival a decade later. Using clips from The Invisible Woman (a 2013 film), he reflected on the play's connections to the unconventional personal lives of both Collins and Dickens.

We went on to discuss several key themes of the play: we explored its presentation of the relationship between destiny and precognition, as epitomised in the striking visions (or 'Claravoyance') of a key character, and links to contemporary interests in spiritualism and clairvoyance (perhaps getting a bit more unfashionable by the mid-1860s?), or the drawing of lots between officers and men; we looked at the work's theatricality (for instance in its staged vision), its drama and melodrama, and how even though it is set in a larger Arctic landscape its acts present a series of three interlinked chamber pieces with quite domestic situations, and the intervening perils only alluded to through (characteristically clunky) expository monologues (with a hint of Monty Python, we thought?).

We thought about why the Artic setting might matter, or not? Was it just a conveniently fashionable location, or - with its connotations of peril, extremity, and isolation - did both supernatural phenomena seem closer to the surface, and also deeper emotions and motivations possible to access? The character of Richard Wardour, in particular, seemed key: was he, as Dickens's biographer Claire Tomalin suggested, an opportunity for Dickens to play a man who overcame his instincts to make a final great sacrifice? Was he someone with frozen emotions until galvanised by a particular situation, or hot-headed throughout? Indeed, we explored whether characters (the Dickens influence?) or plot (the Collins influence?) could be seen as the play's primary driving force.

Overall, a lively discussion and very helpful comments from all who attended: thanks to everyone! Next time we move off from the floating ice-sheets to submerge ourselves under the sea with two pieces by Rachel Carson.

Additionally:

Other songs, poems, etc., referred to in our discussion (with special thanks to the Canadians):

'The Cremation of Sam McGee' by Robert W. Service

|

| Simon's cardboard cast, as captured by Charissa. |

Wednesday, May 24, 2017

Recap - Rain

On what was one of the sunniest and warmest days of the year so far, we met to discuss Ray Bradbury's 'Death-By-Rain', or 'The Long Rain'. Liz gave a fantastic introduction, which introduced not only Bradbury's own life and ambitions (to 'prevent' not just to 'predict' the future), and the film version of the set text (see above), but also set 'The Long Rain' in a context of 1920s-1960s Venus stories. Based on observations of the planet's cloud cover, these tales often depicted Venus as a water-world: a tropical jungle, humid, warm, and uniform, akin to a prehistoric Earth. Bradbury's story - Liz showed - used this setting for a extreme adventure narrative, looking at the psychological and sensory experiences of people trying to navigate such an unforgiving landscape.

Our discussion followed on from these themes, to explore how Bradbury focused on the reactions of his militaristic men to the situation they were in (with, perhaps, slight inconsistencies or unanswered questions of plot or detail), rather than providing an omniscient overview. We looked at his ways of describing the rain - whether through the repetition of the word 'rain', to place the reader, like his characters, under its ceaseless or even torturing presence; or through passages where the rain took on more of a character or agency, posing for photographs, turning into monstrous forms and storms. We considered how the protagonists became unmoored in time and space, with fast-growing vegetation and aimless wandering, bleached- and leached-out bodies and hopeless futures; and wondered what on earth (or on Venus) they were doing there. Finally, we considered the story's ambiguous ending: was the heavenly-sounding Sun Dome just too good to be true?

Our next meeting - continuing to be seasonally inappropriate, and to think about extreme adventures - will be a discussion of The Frozen Deep.

Wednesday, May 10, 2017

Recap - River

We began our term's readings with 'water's soliloquy', the wonderful Dart by Alice Oswald. A lively conversation flowed - just like the poem's Protean protagonist (Proteagonist?) - from voice to voice, place to place, topic to topic, well-chosen word to well-chosen word.

Sound loomed large: we foregrounded the poem's connections to oral traditions and its effectiveness when spoken out loud; we considered Oswald's research process recording a variety of interviews to ensure the poem was 'made from the language of people who live and work on the Dart', 'who know the river'; we reflected on her mental compositional practices while constructing her 'sound-map', or 'songline'.

Drawing these voices together into the 'mutterings' of the river provided a sense of shifts in perspectives and of being somewhat adrift in time: former trades and industries of the region sat alongside cutting-edge technologies (both commercial and leisurewear). However, we felt the poem avoided nostalgia or sentimentalism; indeed, its commitment to evoking a particular multifaceted landscape prompted a more nuanced set of environmental concerns. (We felt we would come back to these more ecological or political concerns when reading Rachel Carson later in the term.)

The glimpses of people or views moved past the reader, some members of the group thought, like those glimpsed through the window of a train - just enough detail for each person to make them feel like a rounded character, but leaving one wanting more. All of these different voices, we felt, claimed an ownership of the river, or at least a synecdochic part of it (a bank, a bend), as theirs. The reliance on the river, and its central place in their lives, was clear, and our thoughts on this topic were immeasurably enhanced by the contributions of two participants who had grown up around the Dart. They agreed that there was a sense of place specific to this river, and which Oswald had been able to capture and convey.

The reading experiences of group members were shared, whether rushing through, revelling in its sounds and imagery, before returning with a more deliberate approach to Oswald's unusual but apposite vocabulary; or being confronted by the poem's difficulty, and considering the problems of translation. Throughout, it was felt the poem's interconnectedness and interdisciplinary nature, drawing on myth, memory, or even the natural historical gory spectacle of an eel eating its way out of a heron (yuck!), shows how the river brings together these voices, images, vocabularies, and authorities as complementary sources of expertise, while paying homage to the wider connotation of rivers as lifeblood.

Overall, then, a marvellous session to start the term, and a pleasure to see new, familiar, and returning participants. Next, we face the Venusian rain, and I'm not sure a brolly will be enough to protect you...

Tuesday, March 14, 2017

Recap - Flight

|

| Experiments in photographic aeronautics. |

Using Richard Holmes's Falling Upwards (2013), and Marie Thébaud-Sorger's 'Thomas Baldwin’s Airopaidia, or the Aerial View in Color' in Seeing from Above: The Aerial View in Visual Culture, Mark Dorrian, Frédéric Pousin (eds), (2013), we thought about the new kinds of experiences which Baldwin was trying to convey with his narrative. We felt that Baldwin had communicated well the exhiliration and novel sensory impressions of his flight, though perhaps he had exaggerated its tranquillity. Looking at the extraordinary images which accompany the text helped think about how Baldwin charted his journey, making myriad observations, and also how he was challenged by new aerial perspectives.

We were left wanting to know more about Baldwin himself: though evidently physically present, from top to toe to taste-buds, in the balloon, and clearly familiar with the local Chester landscape, in other ways he was frustratingly absent. We could find out more about his balloon-supplier Lunardi (including his unfortunate inclusion of his pet cat as part of his aerial cargo) than we could about Baldwin. In some ways, then, by combining a very specific account of one balloon voyage with an inclusive narrative voice, Baldwin enabled any of his readers to imagine they were alongside him above the clouds.

Wednesday, February 22, 2017

Recap - Breath

- 'Aero-medical science'

We considered the optimism around new gaseous discoveries and technologies, and the confidence that new kinds of air could be used as therapy and remedy. We explored the Romanticism of this kind of auto-experimentation, and the key role of figures such as Davy and Beddoes, and places such as the Pneumatic Institution. Comparison between epistolary, prose, and our set poetic descriptions of the effects of inhaling nitrous oxide, demonstrated how Polwhele drew on these other accounts, but pushed them to a satiric extreme.

- Scientific poetry

We also set the poem in the context of a long 18thC tradition of verses on the Universe, or Botanic Garden, from Pope to Erasmus Darwin. We thought about the different poetic forms this corpus engaged with: some epic, some didactic, some comic (as here). Overall, we discussed how poetry like this formed a key part of (elite) British scientific culture at the time, including commentary on recent discoveries, and conveying accurate information (via footnotes, etc.). Indeed, the use of footnotes by Polwhele was a key topic of conversation.

- Politics and fashion

We thought about how these publications were written in the shadow of the French Revolution, Terror, and Napoleonic Wars: in its very name the conservative Anti-Jacobin Review (where our text first appeared) echoed these concerns. We discussed the contrasting political commitments of conservative Polwhele with the more progressive politics of Beddoes, etc., hence the criticism of them under the guise of this poem. In general, we also thought about the contemporary fad or fashion for Laughing Gas (songs, satirical prints), and made comparisons with Davy's subsequently fashionable lectures at the Royal Institution.

- The poem's success?

We agreed we had all enjoyed reading the poem, and its often superbly awful choice of rhymes; but that perhaps not all of its references were that easy to 'get', and that not all of its humour survives over two hundred years later. We thought about the different voices and characters of the (real) people depicted, and whether or not the author - with contrasting poetic styles - had succeeded in conveying this variegated and personalised bodily experience effectively. As the only stimulant we had to hand was sugar (in the form of a birthday cake for Simon), perhaps a full answer to that last question was not possible.We closed the evening with the promised performance of two historic songs about Laughing Gas: the songs can be downloaded here and here from the Wellcome Images site.

|

| Yours truly at the piano, with members of the group looking on. Photograph by Charissa. |

|

| Laughing Gas sheet music. Photograph by Charissa. |

Tuesday, February 07, 2017

Recap - Atmosphere

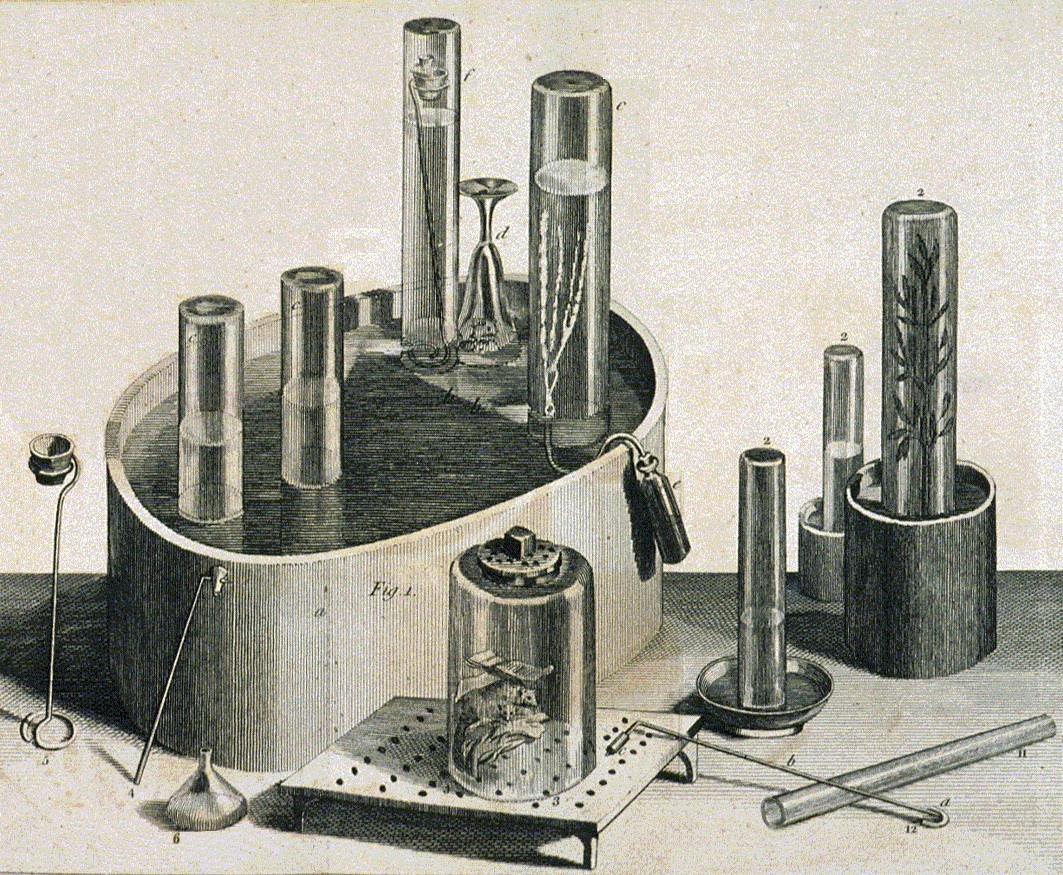

Lent Term began with a suitably sparkling conversation on one of the most important works on air in the history of science, and one of its most interesting characters, Joseph Priestley. In her introduction, Charissa showed the vital role Priestley's Dissenting religious identity played in his life and career, as she traced his biography from England to America via domestic conflagration (perhaps it was too soon to escape last term's theme of fire...). She also gave a brief biography of air, from indivisible classical element to the more complicated understanding of seemingly uniform 'common air' by the eighteenth-century

Our discussion kept returning to the work as a (perhaps slightly fictionalised?) chronicle of the experimental process, guided by sensory experiences, serendipity and an often-surprised narrator. By detailing the apparatus, substances (and creatures), results, and wider ramifications of his researches, Priestley revealed in clear prose how he had been led to his conclusions. His references to other individuals from around Europe demonstrated the interconnectedness of the burgeoning chemical community, and its links to industry. We also thought more generally about chemical language in this period, and the linguistic basis of Lavoisier's reforms in the discipline as providing a new grammar of experiment.

Comparison with Joseph Wright of Derby's An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768) showed a different way in which demonstrative experiments were conducted in this period to varied audiences (and eliciting various reactions): a bird, rather than a mouse, is here subjected to a vacuum:

Considering the fate of Priestley's murine experimental subjects led on well to a reading of 'The Mouse's Petition', on behalf of a mouse 'Found in the trap where he had been confined all night by Dr Priestley, for the sake of making experiments with different kinds of air'. These lines in particular seemed to have a contemporary, as well as an eighteenth-century, political as well as a scientific, resonance:

The well-taught philosophic mindNext time we will stick with late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century pneumatics, but rather than mice being the subject of experimentation on new types of air we will read about what happened when people breathed them in...

To all compassion gives;Casts round the world an equal eye,

And feels for all that lives.

Saturday, December 03, 2016

Recap - Fighting Fire

Last Monday witnessed a fitting finale to the term, when we met to discuss how people have experienced, witnessed, recorded, explained, responded to, dealt with, and even lied about fires.

Our set readings took in a number of literary forms: Pepys's delightful fiery diary, where an evocative account of the Great Fire of London sat alongside more mundane matters; a contemporary ballad both chronicling the geographical spread of the fire but also invoking classical comparison and divine retribution; R.M. Ballantyne's 'Boy's Own'-style adventure, where the fire was cast as an enemy or a wild animal to be conquered by the noble fire brigade and juvenile hero; and Hilaire Belloc's charming cautionary tale, riffing on moral fables for the young.

Several themes of the term's conversations therefore recurred: the liveliness of fire, and the temptation to anthropomorphise it; the wider spiritual and religious symbolism of fire; attempts to control fire by the use of certain kinds of equipment; how best to describe in verbal or visual forms a far more multisensory experience. Although with twentieth-century comic verse we were perhaps far from Heraclitus, the connecting thread of fire meant that even more similarities or contrasts, echoes and evocations, were present than I had anticipated when setting the readings over the summer. Appropriately, we closed the term as we began, with the reading of a piece of poetry.

Thank you so much to everyone who has contributed to a particularly memorable series of sessions this Michaelmas! As previously advertised, we will be sticking with the elements in Lent when we will be exploring air, possibly now with a focus on eighteenth-century pneumatics. (Readings will follow in January.) Until then, may the Yule log burn bright!

Our set readings took in a number of literary forms: Pepys's delightful fiery diary, where an evocative account of the Great Fire of London sat alongside more mundane matters; a contemporary ballad both chronicling the geographical spread of the fire but also invoking classical comparison and divine retribution; R.M. Ballantyne's 'Boy's Own'-style adventure, where the fire was cast as an enemy or a wild animal to be conquered by the noble fire brigade and juvenile hero; and Hilaire Belloc's charming cautionary tale, riffing on moral fables for the young.

Several themes of the term's conversations therefore recurred: the liveliness of fire, and the temptation to anthropomorphise it; the wider spiritual and religious symbolism of fire; attempts to control fire by the use of certain kinds of equipment; how best to describe in verbal or visual forms a far more multisensory experience. Although with twentieth-century comic verse we were perhaps far from Heraclitus, the connecting thread of fire meant that even more similarities or contrasts, echoes and evocations, were present than I had anticipated when setting the readings over the summer. Appropriately, we closed the term as we began, with the reading of a piece of poetry.

Thank you so much to everyone who has contributed to a particularly memorable series of sessions this Michaelmas! As previously advertised, we will be sticking with the elements in Lent when we will be exploring air, possibly now with a focus on eighteenth-century pneumatics. (Readings will follow in January.) Until then, may the Yule log burn bright!

Wednesday, November 16, 2016

Recap - Bodily Fire

| |

| Simon's marvellous evocation of the spontaneous combustion scene in Bleak House, as photographed by Charissa. |

Thankfully the signs were reassuring as we entered the

Newnham Grange Seminar Room for the third meeting of term: no smoke, little

soot, a lack of greasy residue, and only the smallest heaps of ash. Despite the

subject-matter of our selected readings, we could be fairly sure that no

spontaneous combustion had occurred. Thus emboldened, and joined by some

two-dimensional Dickensian colleagues, we embarked on a

lively (and largely politics-free…) debate on the fact, fiction, history, and

mystery, of this strange manifestation of bodily fire.

Charissa introduced the chosen extracts from the Philosophical Transactions, Familiar Letters on Chemistry, and Bleak House, detailing the specific

connections they drew upon: medicine and chemistry; science and the

law; certain kinds of people and particularly fiery fates. These lines of

approach opened up rewarding topics of discussion, from the set of clues or

symptoms (see Huxley's 'Method of Zadig') of spontaneous human combustion, to varying explanations for its

supposed occurrence, internal and external (lightning, gin, internal gases?), to whether or not a realist novel

had to include realistic science.

An evocative reading by Simon of the opening pages of Bleak House reminded us of the atmosphere and wider preoccupations of the work, including its general preoccupation with combustion, energy and entropy (for more on this, see Barri Gold's Thermopoetics), driving the engine of its plot. This led us on to a perennial topic of interest for the group: the role of models, analogies, and lived experiences more generally in scientific writings and conceptualisations.

Expertise was another key area of interest: Liebig's setting-up of hierarchies in his piece of chemical (and chemists') advocacy, and his connections to training a generation of research chemists; how links to industry, agriculture, and the state, helped affirm the role of the scientific expert. We thought about the relationships between scientific experts and the public (would people no longer send in 'curious observations' directly to the Royal Society?), between scientific experts and expert witnesses (are mathematicians no longer permitted as expert witnesses?)

We discussed how different this type of fire was, compared with its incarnations in our earlier sessions: no longer as pure, generative, creative, as in Heraclitus, nor as subtle as in Barrett and Tyndall; however, in its associations with fate ('The Appointed Time') and hell-fire it retained a spiritualised or divine element. Finally, we also thought about the more recent examples of 'SHC', as it has become known; its occurrence in recent sci-fi and fantasy works, including Buffy, X-Files, and Red Dwarf, and whether it is now more usually found in the province of conspiracy theorists than serious scientific enquiry. But the question remains: is spontaneous human combustion impossible, or just very very improbable?

Expertise was another key area of interest: Liebig's setting-up of hierarchies in his piece of chemical (and chemists') advocacy, and his connections to training a generation of research chemists; how links to industry, agriculture, and the state, helped affirm the role of the scientific expert. We thought about the relationships between scientific experts and the public (would people no longer send in 'curious observations' directly to the Royal Society?), between scientific experts and expert witnesses (are mathematicians no longer permitted as expert witnesses?)

We discussed how different this type of fire was, compared with its incarnations in our earlier sessions: no longer as pure, generative, creative, as in Heraclitus, nor as subtle as in Barrett and Tyndall; however, in its associations with fate ('The Appointed Time') and hell-fire it retained a spiritualised or divine element. Finally, we also thought about the more recent examples of 'SHC', as it has become known; its occurrence in recent sci-fi and fantasy works, including Buffy, X-Files, and Red Dwarf, and whether it is now more usually found in the province of conspiracy theorists than serious scientific enquiry. But the question remains: is spontaneous human combustion impossible, or just very very improbable?

Thanks, as ever, to all who contributed to a particularly enjoyable evening!

Wednesday, November 02, 2016

Recap - Sensitive Fire

Thanks to all who forewent an opportunity to trick or treat, and instead attended our Hallowe'en meeting of the Science and Literature Reading Group on Monday evening! We formed another excellently interdisciplinary group, with a particularly strong showing from the HPS MPhil and Part III cohort, which committed itself to a conversation about experimental practice, paranormal activity, natural classification systems, and public engagement techniques from the 18th century to the present day.

In my introduction I tried to draw out three main ways in which to think about these readings about the so-called sensitive flames: phenomena, genre, and community. Phenomena: how do you interrogate, explain, and describe what happens in the (super)natural world? Genre: what is particular about publishing in the late-19th-century periodical press? Are these articles more lectures, essays, attempts at virtual witnessing? How do the poems, and articles, relate to each other? Community: how literature as well as science binds together communities, how communities were defining themselves at this time: British Association, physicists, men of science, spiritualists, etc.

Many of these issues, I suggested, were to do with boundaries: a theme which opened up the discussion: we talked about the style in which Tyndall's piece was written, with the sensitive flame almost like a living creature; how a taxonomy of flames was created; we watched a video of a sensitive flame in action; we talked about what kinds of forces were involved, and how the effects were explained; we considered the special role that flames and candles had at the Royal Institution, and its particular place within the London scientific landscape of the 19th century; we connected these readings back to Heraclitean understandings of flux and change, spirit and matter; how Tennyson's 'The Brook' could be rewritten as a series of celebratory scientific in-jokes; and what limits (or not) there might be to what experimental approaches could reveal about the workings of the universe.

Thanks to all who contributed to the discussion or to the catering arrangements, which with their zombie brain jellies or DIY 'sensitive flame' biscuits made up for any Hallowe'en festivities we might have been missing out on. And the supernatural theme will continue next time, when we discuss spontaneous human combustion...

In my introduction I tried to draw out three main ways in which to think about these readings about the so-called sensitive flames: phenomena, genre, and community. Phenomena: how do you interrogate, explain, and describe what happens in the (super)natural world? Genre: what is particular about publishing in the late-19th-century periodical press? Are these articles more lectures, essays, attempts at virtual witnessing? How do the poems, and articles, relate to each other? Community: how literature as well as science binds together communities, how communities were defining themselves at this time: British Association, physicists, men of science, spiritualists, etc.

Many of these issues, I suggested, were to do with boundaries: a theme which opened up the discussion: we talked about the style in which Tyndall's piece was written, with the sensitive flame almost like a living creature; how a taxonomy of flames was created; we watched a video of a sensitive flame in action; we talked about what kinds of forces were involved, and how the effects were explained; we considered the special role that flames and candles had at the Royal Institution, and its particular place within the London scientific landscape of the 19th century; we connected these readings back to Heraclitean understandings of flux and change, spirit and matter; how Tennyson's 'The Brook' could be rewritten as a series of celebratory scientific in-jokes; and what limits (or not) there might be to what experimental approaches could reveal about the workings of the universe.

Thanks to all who contributed to the discussion or to the catering arrangements, which with their zombie brain jellies or DIY 'sensitive flame' biscuits made up for any Hallowe'en festivities we might have been missing out on. And the supernatural theme will continue next time, when we discuss spontaneous human combustion...

Tuesday, October 18, 2016

Recap - Cosmic Fire

Our first fiery discussion of the term delved deep into Heraclitean philosophy, as we sought an understanding of his cosmology. Whether considering flux or balance, mensuration or childishness, it was clear that our hour-and-a-half discussion was only ever going to be a beginning to a longer journey of reflection on allusive sayings and elusive meanings (I feel Heraclitus would have approved). Along the way, we were helped by thoughtful and generous contributions from our numerous, wide-ranging group of attendees - thanks to all who came!

Comparing the more academic translation of Heraclitus's fragments with later poetic versions enabled us to foreground the form of his philosophy: suggestive, rather than didactic, perhaps? Like nature's hidden meanings, did true wisdom also have an occult quality? Should it more fruitfully be compared with contemporary Daoist writings, rather than Greek sophistry? A fine reading of Gerard Manley Hopkins brought out new textures to his poem, and after dwelling on the spiritual elements of Heraclitus's writings, we were able to see how its ideals of change, becoming, and conflagration could be co-opted in imagery of the Christian resurrection. Indeed, how metaphorical, and how literal, Heraclitus's fire might have been formed another hot topic of discussion: in a characteristic move for the Reading Group, this led to both a frantic Googling of the history of scorched earth agriculture, and a meditation on the etymology and linguistic co-locations (and collocations) of fire with anger, life, or love.

All this, and much more (I haven't even mentioned Nietzsche): our interest in this topic has certainly been kindled.

Comparing the more academic translation of Heraclitus's fragments with later poetic versions enabled us to foreground the form of his philosophy: suggestive, rather than didactic, perhaps? Like nature's hidden meanings, did true wisdom also have an occult quality? Should it more fruitfully be compared with contemporary Daoist writings, rather than Greek sophistry? A fine reading of Gerard Manley Hopkins brought out new textures to his poem, and after dwelling on the spiritual elements of Heraclitus's writings, we were able to see how its ideals of change, becoming, and conflagration could be co-opted in imagery of the Christian resurrection. Indeed, how metaphorical, and how literal, Heraclitus's fire might have been formed another hot topic of discussion: in a characteristic move for the Reading Group, this led to both a frantic Googling of the history of scorched earth agriculture, and a meditation on the etymology and linguistic co-locations (and collocations) of fire with anger, life, or love.

All this, and much more (I haven't even mentioned Nietzsche): our interest in this topic has certainly been kindled.

Monday, July 04, 2016

Recap - Frogs

| F is for Frog, in Walter Crane's Absurd A.B.C. |

Speaking of cartoonish depictions, several of us also met for an additional event: a screening of Disney's version of The Princess and the Frog, accompanied by suitable New Orleans cuisine. The ideal end to the term!

| Many connections to our term's discussions were found when viewing Disney's The Princess and the Frog. |

|

| A recent visitor to our garden. |

Monday, June 13, 2016

Thursday, May 19, 2016

Recap - 16th May

After a round of introductions (and a welcome to new attendees), Charissa began our second meeting of term by detailing the long history of frogs and experiments. She guided us through everything from early modern ponderings over how frogs reproduced, to testing with taffeta trousers, twitching when connected to electrical circuitry, and their more recent role as a model organism. Turning to the reading, she discussed how Sedgwick's piece went through the history of this (gruesome?) experiment, before adding its own findings: the insight this gave into experimental physiology in the 1880s, how it related to other research ongoing in homes and laboratories in Europe and North America, and how it should be written about.

The rest of the evening's conversation ranged from materialism to metamorphosis: we looked, amongst other things, at the article's tone of voice (almost Jane Austen-ish at times? at other times especially evocative words break through the overall dispassionate approach) and literary style of the journal article, which gave insights into its historical positioning between something written for a generalised periodical audience, and a more specific piece of scientific literature for a community of experts; we thought about model organisms more generally as analogies; we considered the contemporary vivsection debates and how considerations of the ethics and emotions of animal experimentation were brought into play (or not) in reports such as this; indeed, we wondered whether it mattered whether this was a frog at all: it was, rather, part of the apparatus, an experimental organism which was an abstracted reflex mechanism, brainless or brained; we considered the lack of information about what type of frog it was, and how the varied natural history (or availability - where did these frogs come from?) was not considered important in the experimental description; how the frog was used to connect up different levels of research into temperature, from cellular to seasonal effects; and the consequences of both evolutionary and philosophical considerations of the status of animals as to the relationships between spirit and matter. And, in a glimpse of what we're going to be talking about next time, we talked briefly about other ways in which frogs appeared in scientific literature in the nineteenth century, including natural history books for children which encouraged actual encounters with frogs, and stories in which the frogs, in a different way to their use as model organisms or parts of experimental apparatus, appeared as analogies.

Links to other pieces of writing mentioned in the discussion:

| Frogs as one of a series of model organisms. |

Links to other pieces of writing mentioned in the discussion:

- Thomas Henry Huxley on 'Has a Frog a Soul?' to the Metaphysical Society in November 1870

- Charles Darwin's Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872)

- Frog hunting in John Steinbeck's Cannery Row (1945)

Tuesday, May 03, 2016

Recap - 2nd May

| The frog in Conrad Gesner's Historiae animalium (published from 1551-87) |

We went on to explore various themes and topics raised in the text, from Biblical plagues to magical applications and onomatopoeic poetry. Topsell, we saw, drew especially from ancient authorities, but in bringing together his text-based research he was not afraid to question their accuracy, and to deploy more recent arguments where necessary. We wondered who would have bought and read this book, and why, whether seeking a comprehensive distilliation of known wisdom on the frog, an imaginative flight of fancy, or perhaps (and the index, as John pointed out, seemed to support this) medical advice on how to cure any manner of ailments.

All of these discussions were accompanied, of course, by suitable refreshments: a more modern emblem of 'frogness', Freddo.

|

| Essential themed snacks. |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)